Beginning Programming in Python

Fall 2019

Agenda

- Tuples

- Lists

- List comprehensions

- Iterators vs. lists

- Generators and the yield keyword

tuples

- An ordered sequence of elements, can mix element types

- Cannot change element values, "immutable"

- Represented with parentheses

# A tuple

x = ("Paris Hilton", 1981)

type(x)

# You can address the members of a tuple using indices

x[0]

# A tuple of length one is specified like this

x = (1,)

# Note x is not a tuple here, as the interpretor just simplifies out the brackets

x = (1)

# Slicing works just like with strings:

x = ("a", "sequence", "of", "strings")

x[1:]

tuples

- Conveniently used to swap variable values

- Used to return more than one value from a function

def quotient_and_remainder (x, y):

q = x // y

r = x % y

return (q, r)

(quot, rem) = quotient_and_remainder (4, 5)

tuples

- Immutable

- Length

- In operator

julia = ("Julia", "Roberts", 1967, "Duplicity", 2009, "Actress", "Atlanta, Georgia")

len(julia) # The length of the tuple

x = ("a", "sequence", "of", "strings")

x[0] = "the" # Error

# To make edited tuples from existing tuples you therefore slice and dice them

print(("the",) + x[1:])# Like strings we can do search in tuples using the in operator:

5 in (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

5 not in (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)Tuple assignment

Multiple return values

Nested/composed tuples

tuple comparison

Lists

- An ordered sequence of information, accessible by index

- A list is denoted by sequence brackets "[ ]"

- A list contains elements

- Usually homogeneous

- Can contain mixed types

- List elements can be changed, so a list is mutable

List functions - review

5 minutes break!

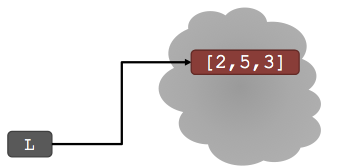

Lists are mutable

- Lists are mutable

- Assigning to an element at an index changes the value

- L is now [2, 5, 3], note this is the same object L

L = [2, 1, 3]

L[1] = 5

List mutability

Conversion and nesting

Aliasing vs. cloning

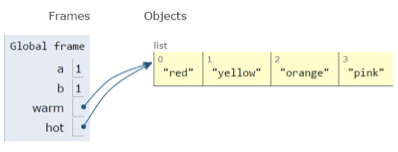

aliasing

0

Advanced issues found▲

- "hot" is an alias for "warm" - changing one changes the other

- For example, here "append" has a side effect

a = 1

b = a

print(a)

print(b)

warm = ['red', 'yellow', 'orange']

hot = warm

hot.append('pink')

print(hot)

print(warm)

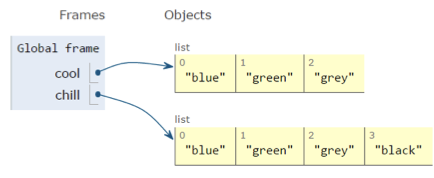

cloning

0

Advanced issues found▲

- Create a new list and copy every element using

cool = ['blue', 'green', 'gray']

chill = cool[:]

chill.append('black')

print(chill)

print(cool)

chill = cool[:]

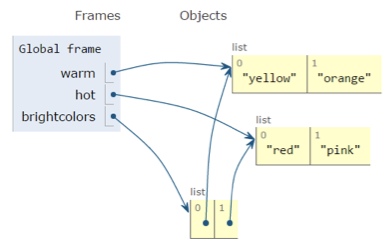

lists of lists of lists of ...

0

Advanced issues found▲

- We can have nested lists

warm = ['yellow', 'orange']

hot = ['red']

brightcolors = []

brightcolors.append(warm)

brightcolors.append(hot)

print(brightcolors)

# [['yellow', 'orange'], ['red']]

hot.append('pink')

print(hot)

# ['red', 'pink']

print(brightcolors)

# [['yellow', 'orange'], ['red', 'pink']]

List comprehension

0

Advanced issues found▲

- A super useful mashup of a for loop, a list, and conditionals

x = [ "a", 1, 2, "list"]

# Makes a new list, l, containing only the strings in x

l = [ i for i in x if type(i) == str ]

# The basic structure is:

# [ EXPRESSION1 for x in ITERABLE (optionally) if EXPRESSION2 ]

# it is equivalent to writing:

# l = []

# for x in ITERABLE:

# if EXPRESSION2:

# l.append(EXPRESSION1)list comprehension Example

Iterators vs. lists

-

What's the difference between list(range(100)) and range(100)

-

A range, or iterable object, is a promise to produce a sequence when asked.

-

Why not just make a list? MEMORY

# This requires only the memory for j, i and the Python system

# Compute the sum of integers from 1 (inclusive) to 100 (exclusive)

j = 0

for i in range(100):

j += i

print(j)# Alternatively, this requires memory for j, i and the list of 100 integers:

j = 0

for i in list(range(100)):

j += i

print(j)yield keyword

-

With return you exit a function completely, possibly returning a value. The internal state of the function is lost.

-

Yield is like return, in that you return a value from the function and temporarily the function exits, however, the state of the function is not lost, and the function can be resumed to return more values.

-

This allows a function to act like an iterator over a sequence, where the function incrementally yields values, one for each successive resumption of the function

yield Example

Lecture 8 challenge

Questions?