Beginning Programming in Python

Fall 2019

Agenda

- Items left from previous lectures

- More Functions

- Functions, namespaces, and scope

- Lambda functions

- Functions as arguments

- Optional functional arguments and other tricks

String formatting

'{0}, {1}, {2}'.format('a', 'b', 'c')

# 'a, b, c'

'{}, {}, {}'.format('a', 'b', 'c')

# 'a, b, c'

'{2}, {1}, {0}'.format('a', 'b', 'c')

# 'c, b, a'

'{0}{1}{0}'.format('abra', 'cad')

# 'abracadabra'

string formatting Example

Formatting numbers

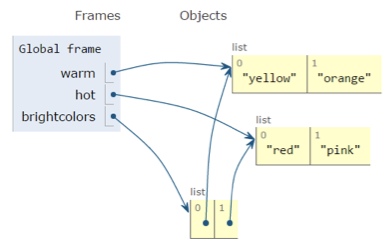

lists of lists of lists of ...

- We can have nested lists

warm = ['yellow', 'orange']

hot = ['red']

brightcolors = []

brightcolors.append(warm)

brightcolors.append(hot)

print(brightcolors)

# [['yellow', 'orange'], ['red']]

hot.append('pink')

print(hot)

# ['red', 'pink']

print(brightcolors)

# [['yellow', 'orange'], ['red', 'pink']]

List comprehension

- A super useful mashup of a for loop, a list, and conditionals

x = [ "a", 1, 2, "list"]

# Makes a new list, l, containing only the strings in x

l = [ i for i in x if type(i) == str ]

# The basic structure is:

# [ EXPRESSION1 for x in ITERABLE (optionally) if EXPRESSION2 ]

# it is equivalent to writing:

# l = []

# for x in ITERABLE:

# if EXPRESSION2:

# l.append(EXPRESSION1)list comprehension Example

Iterators vs. lists

-

What's the difference between list(range(100)) and range(100)

-

A range, or iterable object, is a promise to produce a sequence when asked.

-

Why not just make a list? MEMORY

# This requires only the memory for j, i and the Python system

# Compute the sum of integers from 1 (inclusive) to 100 (exclusive)

j = 0

for i in range(100):

j += i

print(j)# Alternatively, this requires memory for j, i and the list of 100 integers:

j = 0

for i in list(range(100)):

j += i

print(j)yield keyword

-

With return you exit a function completely, possibly returning a value. The internal state of the function is lost.

-

Yield is like return, in that you return a value from the function and temporarily the function exits, however, the state of the function is not lost, and the function can be resumed to return more values.

-

This allows a function to act like an iterator over a sequence, where the function incrementally yields values, one for each successive resumption of the function

yield Example

5 minutes break!

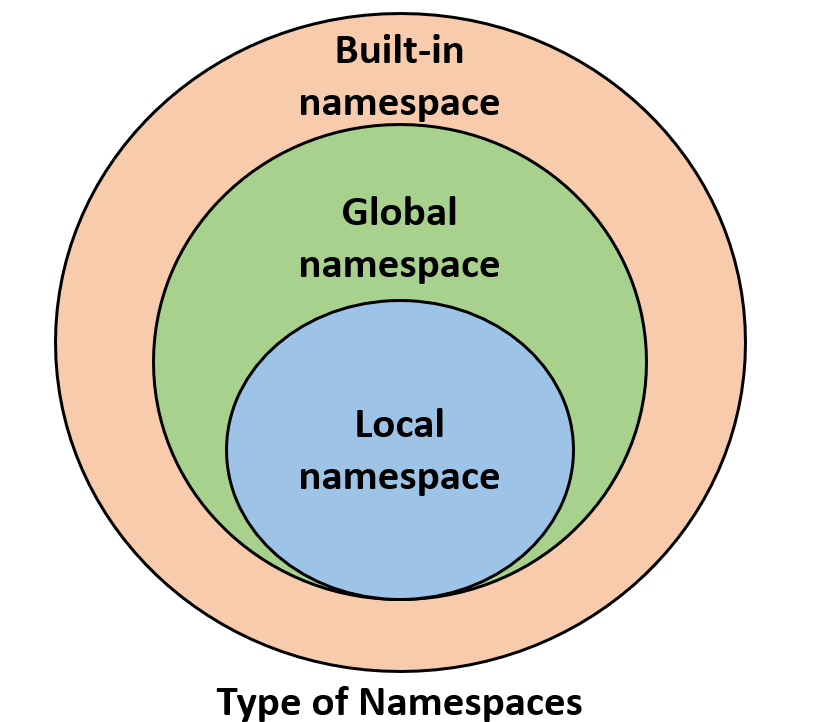

Namespace

-

Namespace is the set of identifiers (variables, functions, etc.) a line of code can refer to.

-

Tiers:

-

Local scope: identifiers within a function

-

Global scope: identifiers declared within the current module

-

Built-in scope: identifiers built into Python - like range, list, etc.

-

Namespace examples

- Local scope:

- Global scope:

- Built-in scope:

def sum(x, y):

z = x + y # x, y and z are in the local scope of the function, they

# are "local variables"

return zs = "hello" # s is in global scope, it is a global variable

def sum(x, y):

z = x + y

return zs = "hello"

def sum(x, y):

z = x + y

return z

w = float(input("enter a number")) # float and input are built-in functions, they are

# in built-in scopeIdentifier definition

print(x)

# This doesn't work because x is not yet defined

# In other words, it is not yet in the "namespace" of this line of code

x = 5- Identifiers should be declared in a namespace before we are able to use them in a statement

Identifier Collision

-

Identifier collisions (identifiers with the same name) are resolved by taking a local scope version in precedence to a global score version, and in turn a global score version in precedence to a built-in scope version, i.e.:

-

local scope > global scope > built-in scope

-

Example

# Let's see how these rules affect an example

x = 5 # Global scope

def sum(w, z):

x = w + z # This copy of x is in local scope

return x

print(sum(5, 10))

print(x) # This copy of x is the global scope versionNAmespace example

Inheriting from an outside scope

Identifier Collision Example

A more complex Example

Lambda function

-

Useful when we define little functions

fn = lambda x, y : x + y > 10

#lambda definition is equivalent to

#def fn(x, y):

# return x + y > 10

fn(5, 10)optional function arguments

When calling a function:

- Must appear in the same order as function header:

- Or, must be used in "name=value" way:

- Or both:

average = average2(100, 50)average = average2(num1=100, num2=50)average = average2(100, num2=50)default argument Example

Lecture 9 challenge

Questions?